By 1948, the federal government began to acquire land and private buildings for the construction of the East Branch Flood Control Project. By this time not a whole lot was left of the once thriving community. Existing structures that remained were demolished or moved and the land cleared for the new lake that would take up behind the newly constructed earthen dam across the East Branch river near Glen Hazel. Soon the town of Straight and it’s sister town of Instanter were flooded and now remain only in memories and under water.

However, during the re-construction of the East Branch Dam, (2008-2021) the water levels of the reservoir often dropped to extremally low depths where the foundations of the former town & CC camps could be located.

The Story of Straight

Editors note: The following story was written by Evan Quinn and appeared in “Tanbark, Alcohol, and Lumber” by Thomes T. Tabor – Book No. 10. The T.H. Quinn and Company was headed by Martin F. Quinn, father of Evan Quinn.

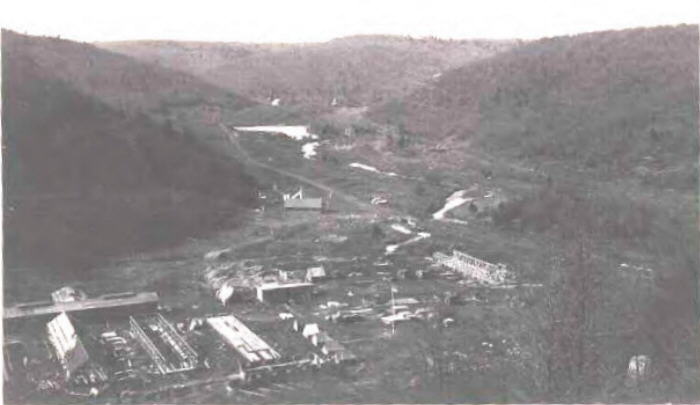

Straight was located two miles south of Instanter on the East Branch of the Clarion River. The Straight Creek flowed in from the east and formed a quarter mile wide valley. About one mile up the creek it split into branches, the North and South Branch which extended easterly each about four and a half miles. The property was approximately 12,000 acres.

Henry, Bayard and Company had planned to divide the two valleys into separate contracts with different contractors each having their own mill. They offered my father one of the parcels. He went over the entire property and after talking with his partners, he said he would build a 75,000 board foot mill, a village, and railroad lines if he could cut the entire property. The Henrys agreed. Father also envisioned a chemical plant for the hardwood.

Father moved us to a log cabin located near the mouth of Straight Creek. It was a big cabin and at one time President Grant had used it for fishing. Father commuted to Quinwood every other day. Once in a while he would take me with him. We would take the morning train up and come back on the afternoon run.

Lumber from Quinwood was used to construct Straight. A camp was built for the large number of Italians who did the pick and shovel work. T. H. took charge of building the railroad which initially was to go up the South Branch.

The first permanent construction was the store and office. They sat in the middle of the valley about a hundred yards east of the Clarion River. The store was about sixty feet wide by one hundred fifty feet with two counters running nearly the entire length and a butcher’s shop at the rear. Behind it was a flour and feed store about the same size as the general store. A cellar ran under the entire building and there was a second floor with a hand operated elevator from cellar ran under the entire building and there was a second floor. M. F. believed in good quality and had no desire to more than break even. The store opened at 6 a.m. and closed at 9 p.m. Every night the employee’s purchased slips went into the office, which adjoined the store, and were debitted against each man’s pay. Payday was once a month, but most employees let it accumulate, only picking up their statement and any money needed for outside purchases. If there was sickness, the store carried them through, and in hardship cases forgave their debt. If they were plain shiftless, the store called it to their attention that they were spending more than they were earning. Usually a man did not know his wife as going overboard, and when he was notified, he usually told the store to limit her purchases.

M. F.’s house sat near the store with two or three acres of lawn around it and fenced in. About one hundred yards south and abutting was the home of T. H. cut into the hill. On the north side of the store was Sherman’s home. Nearby was a pool room and barber shop. Over the pool room was a dance hall where on Saturday nights there were square dances, and later moving pictures were occasionally shown.

An eight foot wide board walk started at T. H.’s home, came by M. F. and ran up the length of the valley. Paralleling it was the railroad, and long it was the mill and lumber yard. The mill pond was about 100 feet wide by 200 feet long and divided by booms to classify logs.

There were several pastures for cows owned by employees. The homes of the workers at each plant tended to cluster near the plant. As built, the mill houses were all about the same — two story with a kitchen, living room, and two bedrooms on the first floor and four bedrooms on the second and above an attic. All had out houses.

At the east end of town near the Straight Creek chemical Plant was the Italian shanty town.

It wasn’t until about 1904 that a Catholic Church was built. Earlier, a large barn had been used for monthly services. I remember that the choir was about 50-50 Catholic and Protestant. Rasselas priest gave the Mass. He usually came Saturday afternoon to hear confessions that evening. Although there were many Italians, few came to Mass, and most of those were wives and daughters. The first school house was used by the Protestants, most of whom were Methodists.

The mill was designed and built by Clark Brothers of Belmont, New York. In the beginning kerosene lanterns with guards were hung throughout the mill, but later, about 1903, an electric generator was installed to light the mill, yard, and store.

To supply the mill the railroad was built up the South Branch to its headwaters on top of the mountain. Logging started at the furtherest end of the property. As cutting advanced down stream, the rails were taken up and laid on North Fork so that when the South Fork was finished being cut, the North Fork Railroad was finished and ready for logging.

Logs were loaded on the skeleton log cars by hand for the first few years, and it was not until 1896 or 1899 that we bought a loader.

As far as the Henrys were concerned, hemlock was all that mattered. Quinn and Company made more from the chemicals.

The hemlock was huge. The contract with Henry, Bayard and Company called for Quinn and Company to cut the hemlock, pee the bark and deliver it to the tannery at Instanter, saw and pile No. 1 hemlock lumber and ship as directed by the Henrys.

The exact origin of the chemical wood factories at Straight is obscure. I believe that father saw the hardwood at Schimmelfeng’s mill at Instanter going to waste and envisioned a wood chemical plant at Straight where Quinn and Company were going. Ultimately there would be three chemical plants at Straight, each owned by a different company. The oldest was the Lackawanna Chemical plant which was located adjacent to the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks.

The January 12, 1898 issue of the “Potter County Journal” stated that T. H. Quinn and Company had built their sawmill at Straight in 1895. The town had sixty families. Beside the sawmill, the Lackawanna Chemical Company had built a chemical factory in 1895 and two other chemical plants were under construction — the Susquehanna Chemical Company and the Straight Creek Chemical Company.

Life at Straight was mostly work. My father was the chief executive. Any employee with a complaint could see him until 10 p.m. He was well respected and the men came to him with their troubles for his advice. This was a six day schedule. Tom Quinn, as woods boss, was loved by the employees. Sid Sherman ran the mill and chemical plants. Under the three partners were the foremen. Bill Fultz ran the sawmill. Jack Kennedy ran the Lackawanna Chemical Company, Tom Pulver ran Susquehanna an later Vandalia, and Carl Ohlman ran Straight Creek. Axel Johnson was the major jobber at Straight.

Most of the loggers and bark peelers were Americans of Swedish descent, but there were also some French Canucks. Cordwood cutters were Swedes, Austrians, Poles, and Italians. Jobbers hired their own men, owned their own gear such as mattresses (made from straw or corn husks), cooking equipment, tin dishes. The camps were restocked twice a week by the supply car. It was a box car with two large doors on each side, and large bunk size shelves. The log train conductor took the order in from the jobbers for supplies. Sides of beef, a dressed hog, barrels of salt pork, crackers, sacks of potatoes, cabbages, beans, onions, barrels of oatmeal, cornmeal, coffee, salt, vinegar, kerosene, and crates of eggs and condensed milk. A second supply car brought out supplies for the horses — oats, hay, straw.

The camps of Italians required Italian bread and the company built a bakery in Straight, got an Italian baker, and turned out the round loaves.

The kindling wood factory, unlike most in Pennsylvania which were controlled b the Blasidells, was owned by the Quinns. But like most kindling wood factories, it burned down and was not replaced.

There was a special boarding house just for the wood hicks who worked there run by Mr. and Mrs. Ferguson.

The acid factories had many immigrants. Italians unloaded chemical wood and loaded the retort trucks.

The office had several bookkeepers — Roy Winslow, “Daddy” Latch, Harry Latch, and Harry Geary. Frank White was M. F.’s personal secretary. Originally father had a woman secretary but she proved dishonest and so he hired White.

The adjacent store was run by a man named Shaffer whose son, Harry, became a locomotive engineer at Straight and Glenfield.

Dr. James E. Rutherford was the doctor until he later moved to Ridgway.

The turn of the century saw Straight at its peak. In February of 1900 the plant of the Straight Creek Chemical Company burned. Other than the roof and walls, there wasn’t much that could be damaged, and it was soon back in operation.

The lower town was quite pretty. One would not think of it as mill town. Sherman’s, M. F., and T. H.’s homes were large and painted with well kept lawns fenced, big stables, and shade trees planted. M. F. had tall poplars, maples, and fruit trees. The school, store and poolroom were painted as were the houses on the far side of the Clarion. Virgin hemlock surrounded the town on the hillsides — these were not cut until the very last days of the sawmill.

The mill and factory houses were not painted but they had running water and natural gas for heating, cooking, and lighting. Each had large lot sufficient for a garden and there was all the free lumber they might want for a cow barn or ice house. The rent was $5.00 a month and $1.50 for all the gas they could use. Wages were $1.75 to $2.50 per day.

The sawmill burned August 5, 1906 but everything around it was saved. As there were several years of lumbering left, a new Clark mill was built which operated until about 1909 when the last of the hemlock was cut. The mill was then dismantled and sold.

The acid factories continued to operate taking off hardwood from the North Fork.

When the Goodyears were cutting northwest of Wellendorf near the North Fork, but on the other side of the (not Pittsburgh) Pittsburg , Shawmut, and Northern Railroad track, Quinn and Company made a deal with the Goodyears to take the chemical wood to our Straight Creek factory. This required a track across the P. S. & N. At that time we did not have our Keystone factory built.

The Shawmut knew what our intentions were, and they placed guards at spots they thought we would attempt to cross at Wellendorf. We sent a crew to Wildwood and started grading toward the Shawmut track. One dark night Quinn and Company went to Wellendorf and installed a crossing. They knew the Shawmut train schedules and they had flagmen stationed in case of an extra. The crossing was built ahead of time and moved to the Shawmut rails. After completing the crossing, Quinn and Company put on guards to buy all our coal from them. A switch was built at Wellendorf and all coal for our locomotive came in that way from the Shawmut down our railroad.

After Schimmelfeng finished logging at Instanter, we built our railroad north to Instanter parallel to the Pennsylvania tracks, and then ran over Schimmelfeng’s no longer used road bed to take out chemical woo on Five and Seven Mile Runs. We operated in that area for many years.

By 1923 we were concerned with the future. Chemical wood was being brought in from Quaker Bridge, New york, and up in the Arcade section near Buffalo. A bowling pin manufactures at Arcade agreed to have us take his waste tops. His timber was along the Arcade and Attica Railroad. In the process of making the agreement, we purchased the railroad. My brother Paul became president and ran it for many years after we had closed at Straight.

We continued to operate at Straight while hunting for a suitable new location, which turned out to be Glenfield, New York. We closed the Straight Creek Chemical plant first in about 1923. A year or two later Susquehanna closed and in 1926 Lackawanna was closed. Some of the chemical equipment, much of the railroad equipment, one Shay locomotive, and many employees moved to Glenfield.

Story Credit:

The Elk Horn

Elk County Historical Society

Vol 14 — No. 3

Winter Issue 1978

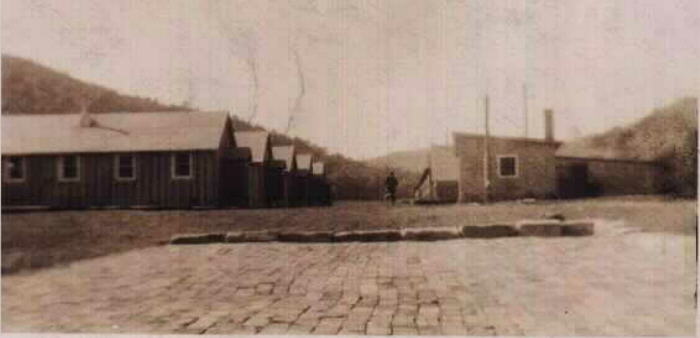

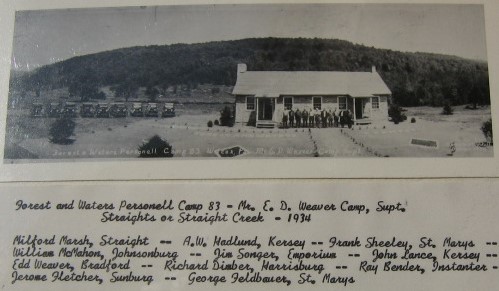

At the former town of Straight, the Federal Government in May of 1933 erected a Civilian Conservation Camp (CCC) for unemployed male youths. The project only lasted about three years.

For many more photos of Straight, please visit the Elk County Genealogy project.